King Charles has acknowledged the “abhorrent and unjustifiable acts of violence committed against Kenyans” during their independence struggle.

On his state visit to Kenya, the King addressed the “wrongdoings” of Britain’s colonial era.

He told a state banquet in Nairobi of his “greatest sorrow and regret” and that there was “no excuse”.

But the King did not deliver a formal apology – which would have to be decided by government ministers.

In response, Kenya’s President William Ruto praised the King’s courage for addressing such “uncomfortable truths”.

The Kenyan head of state told the King that colonial rule had been “brutal and atrocious to African people” and that “much remains to be done in order to achieve full reparations”.

Ahead of the King’s state visit to Kenya, the first to a Commonwealth country since the start of his reign, there had been speculation about a symbolic royal apology.

But if the King stopped short of an apology, his speech in Kenya’s State House was a significant and strongly-worded recognition of the wrongs committed under colonialism.

As Kenya marks its 60th anniversary of independence, the King told his audience: “It matters greatly to me that I should deepen my own understanding of these wrongs, and that I meet some of those whose lives and communities were so grievously affected.”

In particular in Kenya there are memories of the suppression of the Mau Mau uprising, in which thousands were killed and tortured in the 1950s before independence.

A decade ago the UK government voiced its “regrets that these abuses took place” and announced payments of almost £20m to more than 5,000 people, in what it called a “process of reconciliation”.

Monarchs have to speak on the advice of ministers and UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has already rejected calls for an apology on the separate issue of slavery.

The lack of an apology on this trip might have disappointed some Kenyans like David Ngasura of the Kenyan Talai clan.

He has written letters to the Royal Family seeking an apology and reparations – and in response Buckingham Palace referred his request to the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office.

If there are concerns an apology would be interpreted as an admission of liability and lead to legal claims, the Kenyan survivors of the colonial government’s excesses argue it would help bring healing and closure.

King Charles, who delivered a strong acknowledgement of the “most painful times of our long and complex relationship”, told his audience that the friendship between Britain and Kenya could be strengthened by “addressing our history with honesty and openness”.

His comments went further than a speech in Rwanda last year where he spoke of “the depths of his personal sorrow” at the suffering caused by the slave trade.

Part of the King’s speech in Kenya was delivered in Swahili, as he toasted the connections between the countries and remembered the affection his late mother felt for the Kenyan people.

On this first day of the state visit, King Charles had a meeting with President Ruto, visited an urban farm and met young Kenyan tech entrepreneurs.

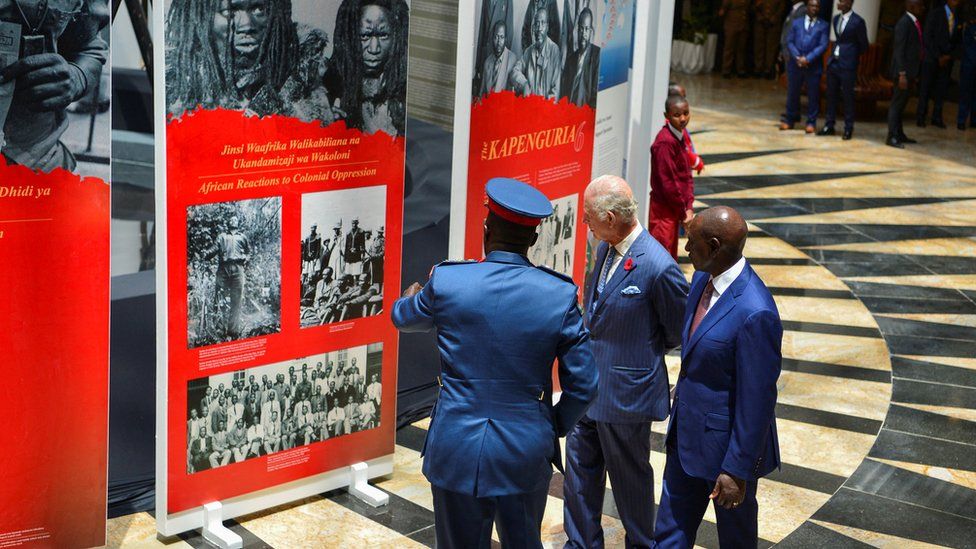

The King also visited a museum dedicated to Kenya’s history and its battle of independence.

The Royal Family, particularly on visits to Commonwealth countries, have increasingly faced questions about the legacies of colonialism and slavery, with calls for apologies and reparations.

Earlier this year, Buckingham Palace said it was supporting independent historical research to examine royal connections to the slave trade.

But newly-published research has revealed a complex picture in royal attitudes towards slavery, with the royal family of the early 1800s divided over abolishing slavery.

The future William IV was a strong pro-slavery advocate, while his cousin the Duke of Gloucester was a leading light of the campaign for abolition.

In the next few days, the state visit to Kenya will focus on ways in which Britain and Kenya are working together, including in tackling climate change and encouraging opportunities and employment for young people.

There will also be a meeting with faith leaders who will talk about building links between communities.