“Prison – far from breaking our spirits – made us more determined to continue with this battle until victory was won.”

27 years in prison

During the 1950s and early 1960s, Nelson Mandela frequently found himself in police station cells, court holding cells, and prison cells for short periods of time, as his political work made him a target for the apartheid regime. After the banning of the African National Congress in 1960, he went underground in 1961 and became the leader of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the armed wing of the Congress. In 1962 he was captured, and sentenced to five years in prison for leaving the country illegally and inciting a strike. In 1963 he joined other MK leaders in the Rivonia Trial, at the end of which he was sentenced to life for sabotage. He was finally released from prison in 1990 after over 27 years of unbroken incarceration. Eighteen of those years were spent on Robben Island.

Sentenced to life imprisonment

Following Nelson Mandela’s sentencing on 7 November 1962 the Pretoria Magistrates Court issued a warrant committing him to prison for five years. He had been convicted and sentenced that day to three years for one charge of “inciting to trespass laws” (to strike) and two for leaving South Africa without a passport. It was stipulated that the two sentences were to run consecutively.

A second Warrant of Committal was issued by the Transvaal Provincial Division of the Supreme Court of South Africa on June 12, 1964, Mr. Mandela and seven others were sentenced to life imprisonment on 12 June 1964. He remained on Robben Island until the end of March 1982 after which he was transferred to Pollsmoor Prison on the mainland. Then, after a few months in hospitals, he was sent to Victor Verster Prison in December 1988 from where he was freed on 11 February 1990.

May 1963: Arriving at Robben Island

This story about Nelson Mandela’s first imprisonment on Robben Island strongly demonstrates his iron will and an indelible sense of dignity that helped him to survive 27 years in prison. He shows, on the one hand, that from day one, the prison warders were determined to treat the prisoners as nothing more than cattle as they tried aggressively to bring them under their control. It was not to be. Mr. Mandela immediately took charge and showed how one can turn the tables even in more dire circumstances. It was this dignity and strength demonstrated by Nelson Mandela and his colleagues later that marked their imprisonment and subsequent demeanor.

May 1963: Remembering the coldest experience in prison

“… We drew strength and sustenance from the knowledge that we were part of a greater humanity than our jailers could claim.”

Nelson Mandela’s prison cell

The 2×2 meter cell in section B of Robben Island Prison, in which Nelson Mandela was held for 18 years.

Prisoners were forced to work in the island’s quarries.

“Prison is itself a tremendous education in the need for patience and perseverance. It is, above all, a test of one’s commitment…”

In the draft of the sequel to his autobiography which he started writing in 1998, Nelson Mandela recalled the harshness of prison life and how his experience as a lawyer before he went to prison helped him to cope. Throughout all his writings from the very early days to even after he had retired, Nelson Mandela was at pains to point out that not every prison warder or apartheid official was bad. This view was underpinned throughout by his assertion that to get along in life one should see the good in all people. It also helped him to choose the right time to initiate talks with the apartheid regime – which was a continuation of efforts made by the African National Congress since the early 1900s and up to 1961.

Removing roadblocks

One of Nelson Mandela’s greatest achievements was his qualification as an attorney. In 1953 he established South Africa’s first black law partnership in Johannesburg with his friend and comrade Oliver Tambo. During his long imprisonment, he used his knowledge of the law to full effect and advantage. His answer to brutality and bullying as well as harassment and abuses was to turn to the law, whether it was on his own behalf or to assist other prisoners: he would either threaten to take action or institute legal action. As this story shows, it became an essential protection.

It would have been easy for Nelson Mandela to allow the world to believe that he was physically assaulted in prison. On the contrary, he has publicly said that it never happened to him. It happened to others but not to him. It would also have been easy for him to tar all the prison guards with the same brush – that they were brutes who would never give an inch. Here Mandela paints a different picture; he talks about how the jailers were not all ‘rogues’ – he makes a point of showing the human and more humane, side of some of his jailers.

Paying tribute to his comrades

Nelson Mandela never hesitated to say that he achieved what he did as part of a “collective” and that his comrades in the African National Congress and particularly those he was in prison with were part of this collective.

Whenever he had the chance he complimented them, as well as those from other political persuasions who suffered with him in prison. He also explained that negotiation was nothing new.

The Release Mandela Campaign

While Mandela and his comrades were imprisoned on South Africa’s notorious Robben Island, efforts to campaign for their release were growing. Since the prisoners were deprived of newspapers for most of the time they were in jail, the campaigners could not expect them to know about their work to publicise their plight.

In this extract from his published autobiographical manuscript written in prison, it is clear that not only was he aware of these efforts – despite stringent censorship of letters and visits, he derived strength from them.

His writing about this issue gave him the opportunity to express his optimism about his eventual freedom and the success of the struggle against apartheid. By the time Nelson Mandela turned 70 – and was still imprisoned – the campaign for his release had reached virtually every corner of the world.

Any and every medium was used to push, coerce, and encourage anyone and everyone to do their bit to help free him. From students and concertgoers to politicians and bankers, most people were touched by the Free Mandela Campaign.

One of the efforts was a series of ten posters by artist Mickey Patel which he donated to the office in India of the African National Congress in exile. One hundred more of these posters were then made from a silk screening.

Twenty-three years later the posters found a home at the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory. They were donated by a former anti-apartheid activist, Mosie Moolla, who escaped from police custody in 1963 and found his way to India where he became the ANC’s Chief Representative in that country.

Keeping strong: letters to his family and lawyers

Heavy censorship of correspondence in prison meant that if a prisoner wanted to communicate anything of a sensitive nature to anyone outside prison they needed to smuggle it out.

1969: secret visits

In a letter to his daughter Zenani to mark her 12th birthday in 1971 Nelson Mandela recalled her birth after his wife had been jailed for 15 days. Like most of his letters to his children, he poignantly tries to be a long-distant father.

Winnie Mandela was pregnant with her eldest daughter when she was arrested for participating in a protest against the passed laws. “Do you understand that you were nearly born in prison?” he writes.

The letter tells her how she was only 25 months old when he went underground and they never lived together again.

He describes one of her secret visits to him in hiding: “I took you into my arms and for about ten minutes we hugged, and kissed and talked. Then suddenly you seemed to have remembered something. You pushed me aside and began searching the room. In a corner, you found the rest of my clothing. After collecting it you gave it to me and asked me to go home. You held my hand for quite some time, pulling desperately and begging me to return.”

1971: Mandela’s thoughts about his family

While in prison Nelson Mandela got information that his wife Winnie was arrested and detained for more than 17 months. From May 1969 to September 1970 she was gone out of their lives and there was nothing he could do to help her or the children she left behind.

At that time their daughters Zeni and Zindzi were aged nine and ten respectively and their father wrote to them from Robben Island trying to comfort them, to be a father. He knew it was highly unlikely that the letter would ever reach them. Luckily he kept a copy in one of two hard-cover notebooks he used to write down the letters he sent.

These notebooks were confiscated by prison warders when he was still on Robben Island but returned to him more than 15 years after his release by a former Security Policeman Donald Card who kept them in his house for years.

1976: Writing to his lawyers

On more than one occasion Mr Mandela and his comrade, Ahmed Kathrada smuggled out letters, especially to lawyers, to complain about conditions in prison.

For example, in January 1977 Mr. Mandela wrote, in tiny handwriting, a long letter to lawyers in Durban instructing them to take action against the prison authorities for a list of instances for “abusing their authority”. The letter was addressed to a firm of attorneys called Seedat Pillay and Co.

In October 2010 one of the attorneys of that firm who became a judge of the High Court of South Africa, Judge Thumba Pillay donated to the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory that letter as well as a series of related documents.

Desk calendars

In his early years in prison, Nelson Mandela and his comrades were forbidden from keeping watches or clocks, and calendars on the wall of his cell. Later he was allowed to order a desk calendar a year from South African Tourism. He kept a series of desk calendars on Robben Island Prison where he was held from 13 June 1964 to 31 March 1982 and in Pollsmoor Prison where he was until 12 August 1988 and to Victor Verster Prison when he was transferred there, until his release on 11 February 1990. He continued recording information in these calendars, while he was in hospital in 1988 – first in Tygerberg Hospital and then in Constantiaberg MediClinic — being treated for tuberculosis. These desk calendars were South African Tourism calendars with scenic photographs and the words “Land of Golden Sunshine”.

Together with his notebooks, the desk calendars are the most direct and unmediated records of his private thoughts and everyday experiences. He did not make entries every day. In fact, there are sometimes weeks where he made none at all. It should be borne in mind that taken-for-granted necessities in the outside world were actually precious luxuries in prison. Milk for tea, for example, was an event. So, too, were visits and letters. And the single word ‘Raid’ masks a deeper menace.

1976: Soweto uprisings

Nelson Mandela and his comrades only heard about this much later when new political prisoners arrived on Robben Island. In the early years on the Island Mandela and his co-prisoners were not allowed any newspapers and did not have a radio.

1977: An arranged media visit

Nelson Mandela notes the visit by the media to Robben Island in 1977. The Apartheid government arranged the visit by journalists to dispel rumors about harsh conditions on the Island.

1977: The prisoner in the garden

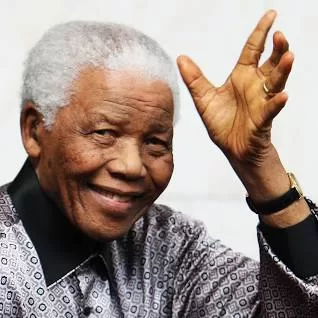

The famous photograph of Madiba was taken on the day the international media was invited by the prison commissioners to Robben Island to observe the prison conditions. This photograph was taken without his consent, and under protest.

1989: De Klerk meeting

On 13 December 1989, Nelson Mandela whilst still in jail met State President F W De Klerk for the first time,

Nelson Mandela at this time agreed to make peace with the apartheid regime and restore multi-racial policies in South Africa, where even Africans we to freely part in nation building of South Africa. Later Nelson became the first elected black president of South Africa where he served one term and retired to focus on work for his NGO the Nelson Mandela Foundation which focused on empowering the youth on many issues.

Kamukama Rukundo Clinton is a Ugandan pan-Africanist, author, and columnist for 1cananews who can be contacted via +256704393540 or rukundopeter33@gmail.com